Economic growth refers to the increase in production or real output of an economy, typically measured by a country’s GDP (Gross Domestic Product). The expansion of output, and thereby GDP, is encouraged through the production and consumption of goods and services in the economy.

Traditionally, economic growth and development are seen as the primary goal of governments across the globe, devoted to the idyllic objective of upgrading their citizens’ living standards.

However, economic growth cannot be discussed in a fair view without considering the environmental contribution to such aspirations. The interlinkages between the environment and economy are manifold; the environment lends its natural resources as inputs for the production of goods and services and also acts as a sink of waste and emissions generated through such economic activities.

Besides the Environment functioning as a driver of economic growth, it is also greatly affected by human activity, which can further influence economic productivity. For example, polluted waterways, lack of clean air, and lost forested areas can impose massive economic costs in the form of unfit labor, increased occurrences of natural disasters, loss of crops, declining animal populations, and so on.

Despite this profound connection between economic growth and the environment, the two are often treated as separate entities, wherein the pursuit of one is seen as an impediment to the progress of the other.

Even with the increased environmental awareness in developing nations, the notion of promoting economic development at the cost of the environment is a well-accepted phenomenon. Most individuals, firms, and governments of developing countries have already surrendered to environmental degradation because of pursuing profits/income.

But if the economy relies so heavily on the environment, why are environmental pleas given a backseat?

To understand this we must first look at the growth pattern of the developed nations. The More Economically Developed Countries (MEDCs) of the globe gained their wealth through a path of environmental destruction. During the 19th and 20th centuries, technological advancements peaked in the West, especially with the onset of the Industrial Revolution wherein their profits and output soared. During the same time, the air quality degraded due to the increased smoke and carbon emissions released from factories, as well as several natural waterways were found polluted. There was an increase in diseases and sickness as the lack of transport systems meant most workers lived suffocatingly close to factories, and large forested and ecologically important areas were destroyed for housing development and agricultural purposes, as well as for procuring raw materials for production.

While the environment suffered, the economy prospered, especially in comparison to the global markets. Eventually, as the average income rose, so did the demand for a better quality of life, which led to the collective realization of environmental significance and its effects on human health. Thereafter rigorous measures were implemented to tighten environmental regulations and reverse existing environmental damages to protect the future health of citizens.

MEDCs have been largely successful in doing so. For instance, the river Thames (situated in the UK) was once considered biologically dead owing to massive pollution, sewage disposal, and industrial waste. However, today it is considered one of the cleanest rivers that passes through a major city, owing to stringent changes in regulations and enormous clean-up efforts undertaken in the 1960’s.

Developing countries are now attempting to emulate this model, employing the tacit assumption that environmental damages can be reversed in the future once economic growth and development goals have been secured.

However, this notion to reverse environmental damages in a delayed future time period can be interpreted as naive, and detrimental to their own future prosperity. This is primarily because we are in the midst of a climate crisis. In the last century, humans have consumed resources, as well as released wastes into the environment at an alarming rate.

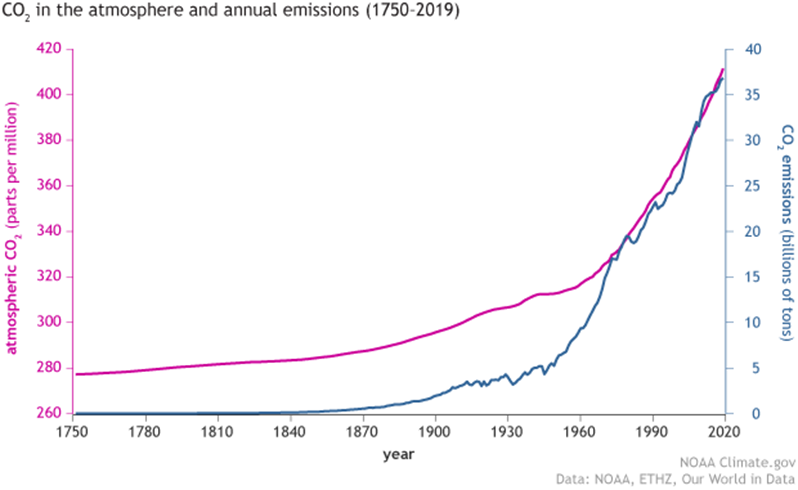

Our CO2 emissions have spiked, with little to no promise of declining anytime soon. Other data suggests that we are likely to cross the threshold for dangerous warming (+1.5 C) between 2027 and 2042. Species are being lost at 1000 to 10000 times the normal rate, and our current consumption levels demand 1.6 to 1.7 of Earth’s resources.

We have sufficient evidence to support that if we continue our current ways of living, by the year 2030, we would have caused irreparable damage to the planet.

The reality of climate change and its ramifications are quite frankly daunting, and even more so to developing nations. This is because countries will be disproportionately affected by the consequences of climate change, with developing countries more impacted than their developed counterparts. Unreliable weather patterns, increasing incidences of droughts, floods, etc, are predicted to further the existing issues of hunger, poverty, malnutrition, displacement, and several other issues that are already ravaging the developing world.

Therefore developing countries of today may not have the luxury to follow the path of environmental negligence to achieve economic prosperity. Economic growth and the environment can no longer be looked at in isolation. Doing so can impair the quality of life of future generations, and destroy any hope of a promising future.

The Solution?

Developing countries must look to ‘Sustainable Development’, which focuses on economic development without the depletion of natural resources, as a long-term solution. Unfortunately, this is not easy. Each country’s economy and industry is complex, and years of work, trial & error, and progress have led to the formation of systems and thought processes that are hard to change overnight.

However, change must begin somewhere. Sustainable development requires concentrated and coordinated efforts across industries, with an appropriate government structure that prioritizes the growth of green GDP.

The first step towards transformation would require an introduction of stringent policies and enforcement mechanisms that appropriately penalize polluting practices, and simultaneously encourage green solutions, without discouraging production.

This would involve detailed and unbiased assessments of projects to determine how much environmental degradation is acceptable, and employing strict measures to ensure nothing further is damaged. It would also require the acceptance that certain industries may not be able to modify their practices immediately; Nevertheless, efforts to invest in and explore alternative solutions, as well as countervail the effects of current operations should be established. For instance, companies unable to reduce or eliminate their carbon emissions must be prompted to offset their carbon footprint through tree plantation drives or experiment with CCS (carbon capture and storage) technologies.

This is of course just the tip of the iceberg.

Developing countries also possess some of the world’s most treasured natural resources, such as the Amazon rainforest in Brazil. The rainforest acts as a major carbon sink and is also home to some of the most unique and diverse species of our planet. The destruction of Brazil’s rainforests for the country’s economic growth can, however, be a disastrous venture for the rest of the world, who rely upon the preservation of Brazil’s rainforest as a common service to maintain global temperatures.

Due to this Brazil faces extreme pressure to conserve its rainforests and natural resources, predominantly from the likes of developed countries which are normally more interested in environmental prosperity than underdeveloped countries. This is especially controversial because most developed countries gained their economic advantage by pursuing the reverse.

So should Brazil impede its own economic growth for the preservation of a globally beneficial resource? After all, the climate crisis is a worldwide phenomenon to which every country, especially the global North, is or has been a contributor. Given this unfair burden, MEDCs must consider the development goals of developing countries and compensate for the economic losses associated with not exploiting their natural resources.

This can provide less developed nations with the necessary external support to choose the path of sustainable development without hampering their economic goals.

In this way, the conflict between development and the environment can be dampened, and a more holistic approach to growth can be administered in developing nations.

Want to learn more about how we can balance economic growth with environmental protection?

References:

Cardenas, S. (2021, January 7). When will global warming become irreversible? World Economic Forum.

Gooljar, J. (2019, December 21). Fact Sheet: Global Species Decline. Earth Day.